Why are you reading THAT?

And what statement does it make on your bookshelf?

Goods good for no one

There are books that should be banned. Not banned by some central authority, but banned by you. Books that you should not just stop reading, but take off your bookshelf. Don’t resell, just toss.

I’m talking about books that are as bad as Halloween candy and deserve the same treatment. So I might as well talk about that first. Among the five of them this year, my young children brought back 8.4 lbs of candy (see the scale at the bottom?), exclusive of the small number of pieces we let them consume.

For a brief moment I contemplated that stack of candy. Mental calculation: $40 retail, since it was about $25 for the 5 lb bag of Costco candy we ourselves had purchased, almost all of which remained undistributed as well: 13 lbs total. What a waste! Could I donate it? Eat it over the course of a year?

Just like those books on your shelf that you should ban from your own life, I couldn’t in good conscience plan anything for that candy that would involve human consumption. That night I threw it in the kitchen trash, all 13 lbs.

Lugging the sack out to the garbage can conjured scenes of murderers disposing of body parts. Even though my conscience was clear somehow it still felt wrong, like something my mom would have frowned upon.

Echo chambers

The Devil’s Dictionary, Ambrose Bierce. Now there’s a book to treat like Halloween candy. I’m almost sorry to link to it, but I can’t help myself! To anyone with a mite of belief that Satan is real, you might think banning such a book is a no brainer. After all, it’s not like there’s any subterfuge here. No false advertising. The Devil and his loyal ghost writers have authored a dictionary. Read it at your own peril!

Like many who discover The Dictionary, my path of discovery was via Bierce’s short story, An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge. It is, like several of his other Civil War stories, a masterpiece. For another, read about the captured soldier who wittily philosophizes, “there is really no such thing as dying.”

I feel torn about Bierce in the same way I am torn about my friend the academic of “depths of crackpot illogic” fame. You could state truly of Bierce what I wrote about the academic: “a sensitive and lucid thinker who has written with subtlety” about deeply human issues. Indeed.

And yet, for the teenage me who discovered The Devil’s Dictionary, it was like consuming 8.4 lbs of candy. Daily. For years. So perfect was the book’s synchronicity with my metaphysical rejection of the spiritual world, and antagonism towards Christianity in particular, that I saw it as prophetic perfection: a pithy summary from a visionary of the past who saw the pathetic lies of religion for what they were. Add to that that Bierce was a fellow tech skeptic to boot! Consider his definition of the telephone: “An invention of the devil which abrogates some of the advantages of making a disagreeable person keep his distance.”

A man ahead of his time, that Ambrose Bierce! Skewering both technology and religion in one little volume. And so I consumed the candy unskeptically (there’s an irony!) for years. Can I blame the book itself? Not really. It was a custom-built echo chamber for me, amplifying the faulty metaphysics and path of ego I had already chosen for myself.

Gritty reality: just grit

What about Atomised? (with the ‘s’ giving it a zing of sophistication to American readers). I began that book after I’d read Houellebecq’s Submission.

In the latter I had found contemporary political truths I appreciated. Like Bierce, but in a more up-to-date fashion, Houellebecq felt like a prophet for our times. I read Submission with (I thought) the modern aloofness of the Sophisticate: I was a cultural observer of the observer. Houellebecq could flesh out his dissolute character in pornographic prose, but I was above it all. I could see what he was doing and see how it fit into the big puzzle, filling a need to explain to a new generation, in their own pornographic terms, what was happening in gritty reality. A weakness of mine is that I am, like many of my co-generationalists, a sucker for the trope that we need to be awake to gritty reality, prepared to face it, even it is unlike that which we aspire to.

But is there a need, in the interest of scientific exploration, in the interest of knowing What People Talk About, to immerse oneself in a gritty reality that is pornographic? Does the assumption that you are doing it for the sake of scientific cultural observation make it any less corrupting? Houellebecq’s reality is that: both pornographic and inevitably corrupting. Is it a facet of truth about reality? Well, yes, to an extent. No one would deny our present reality is saturated in literal pornography. And many of those around us are fornicating in spirit, in body, or both as they follow the siren song of pornography.

However… do I need a book to amplify that gritty reality, to codify it in type, to put it into high resolution? I never finished Atomised. In a moment of epiphany I saw Houellebecq for who he was: a high-brow pornographer. Not to say without insight, but insights devoid of a spiritual grounding. Not insights that I need on my bookshelf. It went to the same place as the Halloween candy.

Taking books off the shelf

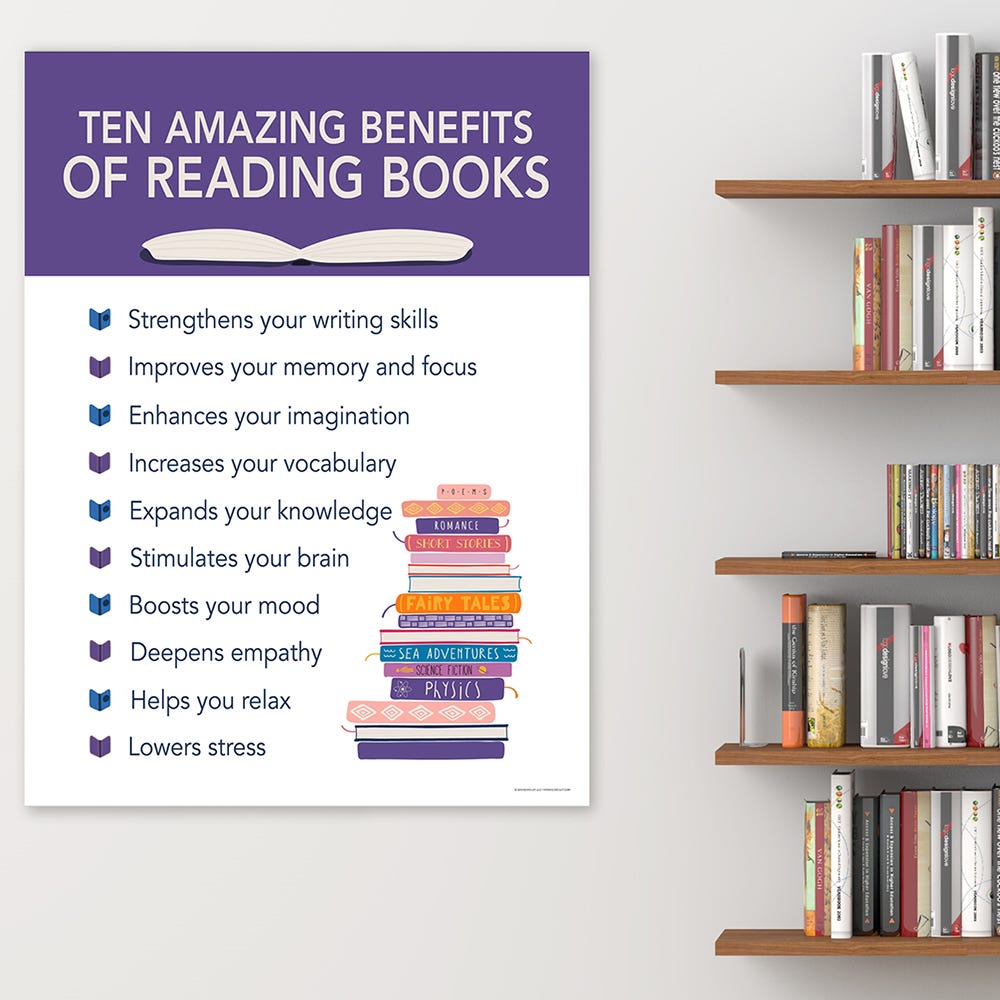

If you were brought up by teachers, librarians, and even parents who promulgated this kind of poster, it’s hard to discard a book.

Nothing special about this one. There are thousands like it. The “no such thing as a bad book” virus is intentionally propagated, even by those who should know better. Back to the candy analogy, it’s like having a calorie lobby. Ten Amazing Benefits of Calories!

Maintains life

Builds muscle

Soothes nerves

Stimulates nerves

…

Never met a calorie you didn’t like, eh?

Back to books, I don’t think I ever quite suffered from the no-bad-book virus. But I did keep books around, both bad books and inane books, under the logic that I had developed some kind of relationship with them (if only to judge that they were inane) and therefore wanted to keep them on my shelf like so many tally marks totaling my intellectual development.

Bookshelf of values

Over the years I eventually had to give up that habit. Residences were moved. Stints were had overseas. Car trunks were filled to capacity. Therefore, books were purged. But for years I did take care to keep the best, by which I meant both those that I liked the most, and those that felt most transgressive. How I loved my relationship with transgression! That included for example the Devil’s Dictionary, even after I’d disowned the spiritual misconceptions in it.

As I think about my clan, though, I doubt the wisdom of that approach.

The bookshelf is something of an endorsement. That’s how I viewed my dad’s bookshelf. As a teenager in search of new ideas, I ventured into his books to find what seemed to me at the time a hidden world of ideas, and hopefully some transgressive ones. I was not disappointed. My dad, a voracious reader of eclectic and undiscriminating tendency, had accumulated books that fulfilled my hopes. Many seem hopelessly dated now. I remember titles like The Naked Ape and Black Like Me.

It is certain my father did not endorse all the ideas in those books. But they were on his shelf, and he never disowned them either. On the one hand, to quote from the poster above, those books did “stimulate my brain.” On the other hand so does meth.

What’s the endgame, then, for those who would like to maintain a library that ennobles the clan, that refines its steel? Do we seek to bowdlerize, to sterilize? I think not. Not only because it would be an impossible purity test—how large would my library be if the standard was that I must agree with every idea in each book?—but because it would backfire anyway. I know from personal experience that the inquisitive youth will seek ideas far and wide. Lacking context for understanding them, and lacking tools to combat the erroneous ideas, he will easily be convinced of the (literally) damnedest things, and encouraged to ferret out even more bad ideas.

Bookshelf purity, then, is not the answer. Better to stretch, to hear sufficiently from other viewpoints. What might have been a subversive idea for an impressionable youth, if encountered in the open with direct confrontation and context, can be stripped of its subversive mystique, rendered merely pathetic. A bookshelf needs to lend itself to a health exploration of ideas.

But that doesn’t mean we have to provide access to Satan’s thought leadership.

For me, a different standard has gradually taking shape, a shockingly simple standard that is less open to the second guessing that I’m apt to give any other standard. It’s so simple as to be a bit of a letdown after all the words written above. At least it would have been a letdown for the old me, who was so enamored of intellectual prowess that he would have demanded a 10-point ironclad standard on what qualifies for the clan bookshelf. The bookshelf commandments would be incisive in their assessments and impervious to critics. Ah, but that’s not where I ended up. Here’s the one rule to rule them all:

Does this book invite the spirit?

I don’t mean the spirit of good vibes, as our new-agey epoch is apt to default to. That’s another essay. We don’t need a bookshelf of feel-good volumes. Never forget that the spirit commanded Nephi to kill a man in cold blood. The spirit that helps me decide on marginal books for the family bookshelf may be the spirit of knowledge or the spirit of truth. It may be the spirit of revelation or of mission. It may be the spirit of vitality or of the sword. What I’m pretty sure it won’t be is the spirit of decadence, conspiracy, or condescension.